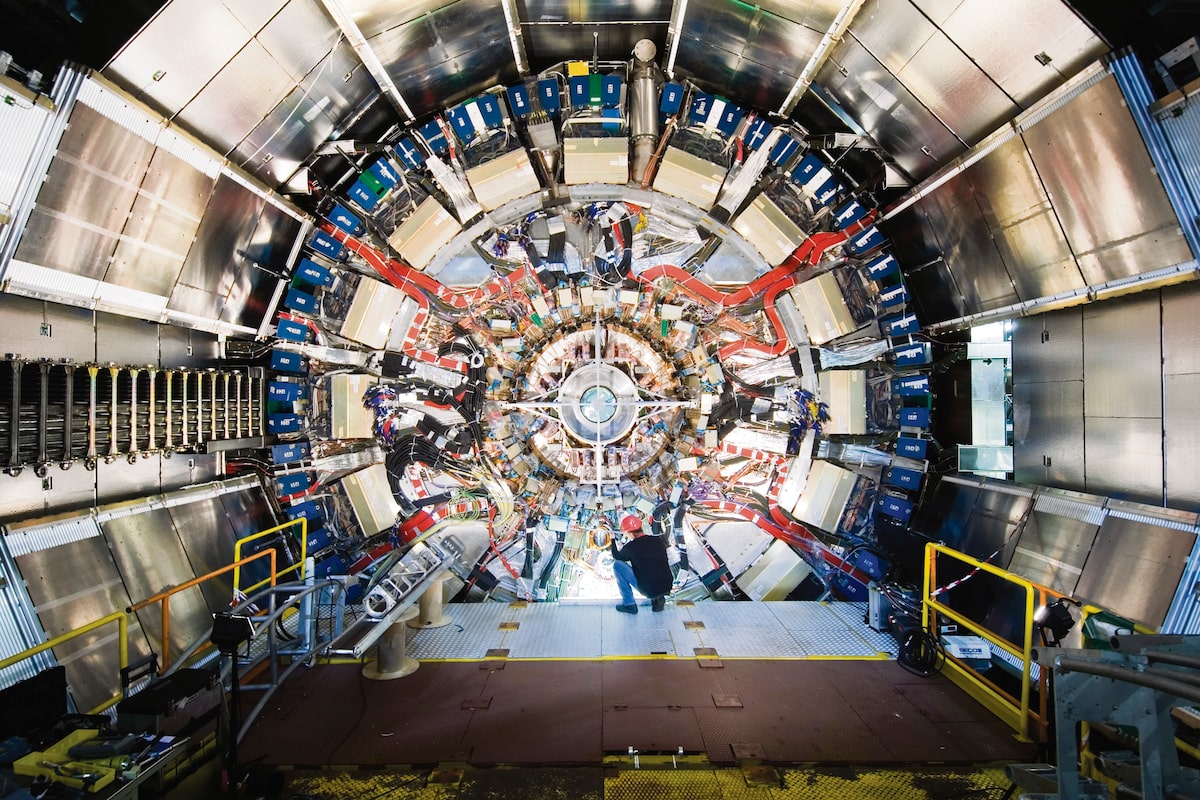

Scientists work on part of the ATLAS mass detector at the Large Hadron Collider during its initial installation in 2007.Claudia Marcelloni/Max Brice

Lawrence M. Krauss, a theoretical physicist, is president of the Origins Project Foundation and host of the The Origins Podcast. His most recent book is The Edge of Knowledge: Unsolved Mysteries of the Cosmos.

Science is, by its very nature, a deeply social endeavor. In the modern world, where the issues scientists are dealing with have become more complex and weightier, the need to harness the intellectual resources of all humanity has never been more important. But this has also opened science to the growing threat of politicization and the pressures that come with it.

The imminent departure of Russian scientists from the European Organization for Nuclear Research’s (CERN) pioneering experiments at the Large Hadron Collider in late November, in response to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, throws into sharp relief the challenge that global geopolitics, and political ideology in general, present to the scientific enterprise.

In the near term, this is a disaster for a group of scientists who themselves bear no responsibility for the actions of their government. Indeed, thousands of Russian scientists signed a petition opposing the invasion shortly after it began. For many of them, their association with CERN has provided a lifeline that has allowed them to continue their research and educate the next generation of students in their country.

I remember visiting Poland to give a lecture shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. There, I met a Polish physicist whose book I had admired. I was shocked to learn that his salary as a faculty member at his institution was insufficient to allow his family to survive. The only way he could continue to conduct research was by spending one month a year at CERN, which provided enough funding to allow him to continue running his research group at home.

Because CERN’s decision not to renew its international cooperation agreement with Russia (and Belarus) was first announced two years ago, many of those scientists have been able to take positions outside of Russia in order to so they can continue their work. While this may resolve their personal issues, it does not address the deeper effect of essentially closing off access to fundamental particle physics research at their former institutions in Russia. A generation of talented young students will now miss out on the opportunity to pursue their academic dreams, and the field will miss out on benefiting from their potentially important contributions.

The loss to science that comes from cutting out a group of people for political or ideological reasons is not just hypothetical. In the case of CERN, it will immediately cause obstacles to ongoing experiments. As Hannes Jung, a German physicist working on an experiment using the Large Hadron Collider, says: “It will leave a hole. I think it’s an illusion to believe that one can cover this much simply from other scientists.”

History is replete with examples of the negative consequences of limiting scientific enterprise on the basis of political ideology. These range from the catastrophic extermination of genetics researchers in Stalinist Russia led by Trofim Lysenko, which resulted in crop failure and subsequent death by starvation, to the arrests and deportations of Jewish scientists in Nazi Germany, which drove Germany from confronting theoretical physics for decades. although this ultimately benefited the rest of Europe and the United States).

I recently heard a direct example of how political obstacles to Russian scientists came close to hindering the progress of science in the field of cosmology, in which I have done much of my work. When I interviewed renowned Russian cosmologist Andrei Linde, who now works at Stanford, for a recent podcast, he shared that it was only the opportunity he once had to travel outside the Soviet Union for a physics conference that led him to develop his main ideas. on cosmic inflation, which he then published in a Western scientific journal. How many young Russian scientists will lose the opportunity to make similar contributions if they are excluded from the global community of scientists?

What may be most worrying about CERN’s decision is that it is not being made in a political vacuum. The incursion of politics into academia is growing along with polarization in the West. There have been widespread calls to boycott Israeli academics and their institutions because of the conflict in Gaza, although many have also opposed their own government’s policies; that didn’t matter to the hundreds of professors in the US and abroad who signed petitions to support such a boycott. Even the American Association of University Professors, which has worked for decades to uphold academic freedom by categorically opposing academic boycotts, recently announced a policy change stating that boycotts of institutions “are not in themselves a violation of academic freedom and can instead be legitimate tactics. responds to conditions that are fundamentally incompatible with the mission of higher education.”

Once the international academic community pursues one country for one reason or another, what is to stop it from pursuing others? Will American scientists be excluded from international collaborations because of the US government’s support for Israel, or because of its various past humiliating attempts to overthrow sovereign governments, including its insidious past efforts in Ukraine?

Science is, or should be, apolitical by its very nature: the universe is what it is, whether we like it or not, and whether or not it conforms to our views of what might be right. The effort to interrogate nature to discover how the universe works and the subsequent development of technologies that have benefited all of humanity must be independent of ideology. While scientists themselves are not free of biases, the scientific process itself ensures that those biases are ultimately unaffected. Science transcends individual scientists, be they good or bad, atheist or religious, Russian or American. It does this by providing a healthy dialectic. No idea is sacrosanct or immune from attack, and the results of experiments—not national sovereignty or political strength—must ultimately judge between competing theories.

Once the floodgates are opened to ideological pressures, such that national origin or political beliefs become a litmus test for participation in the scientific enterprise, the progress of science and scholarship in general is threatened. We are witnessing such dangerous trends in the West already, where, for example, defending biological notions such as the binary nature of sex can lead to academic and social annulment.

Academic freedom is essential, not because academics are special, but because social progress is hindered whenever such freedoms disappear. The scientific enterprise in the 21st century is essentially international. The Internet has leveled the playing field in a wonderful way, allowing young scientists from around the world unprecedented access to cutting-edge research.

In this way, science can unite humanity in ways that few other intellectual pursuits can. There is no Western science, or Eastern science, or Russian science, or NATO science – there is only the universal language of science. Scientists from many countries who speak dozens of languages, worship their own gods, and have potentially conflicting political beliefs speak and understand the same precise mathematical language of science without translation problems or ambiguous misinterpretations. They can work together to break down not only the barriers that nature puts in the way of understanding, but also those created by national and international borders.

CERN’s major experiments such as the Compact Muon Solenoid require the work of thousands of scientists, representing every gender, nationality, race, size and shape of human being. This is an encouraging testament to what is best about the human species: how fear and wonder can unite us to pursue challenges we would otherwise never dream of conquering. When we introduce artificial political divisions that exclude some people from enterprise, in the end we all suffer.